Why It Works

- Removing the backbone makes it easy to flatten the turkey into a single plane, promoting even cooking in the oven, which ensures the light meat and the dark meat reach their optimal cooked temperatures at the same time.

- Since the skin of a spatchcocked bird is all on top, it all crisps up beautifully, giving you more crispy skin than a conventionally cooked bird.

- The removed backbone can be used to give your gravy an extra dimension of turkey flavor.

Serious Eats / J. Kenji López-Alt

If it seems like every year we (along with every other food magazine and blog) come out with a brand new turkey recipe for Thanksgiving, exclaiming “this is the best one, hands down, I swear on my not-yet-dead mother’s future grave!” that’s because we do. If you follow this sort of irresponsible behavior to its rational end, then the only conclusion is that every year, the average quality of roast turkey is progressing on a sure and steady upward path toward perfection.

Serious Eats / Fred Hardy

Or, you may conclude that we food writers tend to exaggerate a wee bit. You would not be wrong in this assessment, but the truth is that there’s no one best way to cook a turkey, and anybody who tells you different is selling something. There are a near endless supply of end goals and restrictions based on the tastes, skills, and time constraints of different home cooks.

This is good news for people like me, because it means that I have a near endless supply of Thanksgiving day scenarios to tackle.

Some people want the perfect golden brown centerpiece in the middle of the table. Some want exotic flavors and spices permeating their meat. Still others care only of moist meat, pushing even the crispest, crackliest, saltiest bits of skin off to the side of their plate (we shall speak no more of these heathen).

This particular method is for folks who don’t give a damn about whether or not the whole, barely-adulterated bird makes an appearance at the table, but want the fastest, quickest, easiest route to juicy meat, and ultra-crisp skin. Basically, it’s a method for lazy folks with great taste. Sound like you? Then come along with me.

Turkey Troubles: How to Cook a Turkey Quickly and Evenly

We all know the basic problem with roasting a whole turkey or chicken, right? It lies in the fact that while leg meat, with its connective tissue, fat, and deep color should be cooked to at least 165°F to be palatable, lean breast meat will completely dry out much above 150°F.*

*The USDA recommends significantly higher temperatures for roast poultry, but given proper resting, 150°F is perfectly safe.

Compounding that issue, you have this problem:

Serious Eats

With a regular turkey, the breast is totally exposed, while the legs are relatively protected. Unless drastic measures are taken, you don’t stand a chance of getting it all to finish cooking at the same time.

So how do you get your turkey to cook evenly, cook faster, and taste better all in one fell swoop? Spatchcock the sucker.

What Is Spatchcocking?

Spatchcocking your bird—that is, cutting out the backbone and laying it flat—solves all of these problems, and then some. The basics for butterflying a turkey couldn’t be simpler.

All you’ve got to do is cut out the turkey’s back with a pair of solid poultry shears. Start by patting the turkey dry with paper towels, then place it breast-side down on the cutting board. Holding it firmly with one hand, make a cut along one side of the backbone, starting down near where the thighs meet the tail.

Serious Eats

Continue cutting, working your way around the thigh joint until you’ve snipped through every rib bone and completely split the turkey up to the neck. Use your hands the spread the turkey open slightly.

Serious Eats

Then make an identical cut along the other side of the backbone. This cut is a little trickier, so make sure not to get your fingers in the way of the blade. Using a clean dish towel or rag to hold on to the bird will make it easier to keep control. Once you’ve removed the backbone entirely, you should remove a large hood of fat up near the neck, if it’s there. And if you wish to make carving even easier, the wishbone can also be removed by making a thin incision with the tip of a paring knife or boning knife along both sides of it, and pulling it out with your fingers.

Serious Eats

Turn the turkey over onto what once was its back, splaying its legs out in a manner that can only be described as inappropriate. Press down hard on the ridge of the breast bone. You should hear a couple of cracks, and the turkey should now rest flatter. Flatter is better for even cooking and crisper skin. Finally, tuck the wing tips behind the breast. This step is not strictly necessary, but it’ll prevent your turkey from looking like it wants to give you a high five as it roasts.

Now you’re ready to lay it flat on a rack set in a rimmed baking sheet.

If you do better with a video guide, the complete instructions are contained in the video below:

Knife Skills: How to Spatchcock a Turkey

What sort of advantages does spatchcocking offer? Well, glad you asked.

Why Spatchcock a Turkey?

Advantage 1: Flat Shape = Even Cooking

By laying the bird out flat and spreading the legs out to the sides, what was once the most protected part of the bird (the thighs and drumsticks) are now the most exposed. This means that they cook faster—precisely what you want when your goal is cooking the dark meat to a higher temperature than light meat.

As a bonus, it doesn’t take up nearly as much vertical space in your oven, which means that if you wanted to, you could even cook two birds at once. This is a much better strategy for moist meat than trying to cook one massive bird.

Advantage 2: All Skin on Top = Juicier Meat and Crisper Skin

A regular turkey can be approximated as a sphere with meat inside and skin on the outside. Because it’s resting on top of a roasting pan or baking sheet, one side of that sphere will always cook more than the other.

A spatchcocked turkey, on the other hand, resembles a cuboid, in which the top surface is skin and the volume is meat. This leads to three end results. First, all of the skin is exposed to the full heat of the oven at the same time. There is no skin hiding underneath, no underbelly to worry about. Secondly, there is ample room for rendering fat to drip out from under the skin and into the pan below. This makes for skin that ends up thinner and crisper in the end.

Finally, all of that dripping fat bastes the meat as it cooks, helping it to cook more evenly, and creating a temperature buffer, protecting the meat from drying out.

Advantage 3: Thinner Profile = Faster Cooking

A normal roast turkey can take several hours to cook through at an oven temperature of around 350°F or so. Try and increase that heat, and you end up scorching the skin before the meat has had a chance to cook through.

With a spatchcocked turkey and its slim profile, this is not a problem. You can blast it at 450°F and it’ll cook through in about 80 minutes without even burning the skin. In fact, you want to cook it at this temperature to ensure that the legs and breasts end up cooking at the same time (lower heat leads to a lower differential in the internal temperature between hot and cool spots), and that the skin crisps up properly.

It’s a time savings of about 50%! If I added up all the time I could have saved in Thanksgivings past using this method, I could perhaps—dare I say it—rule the world?

Advantage 4: Turkey Backbones = Better Gravy

It’s always possible to make gravy with nothing but canned chicken stock and drippings, but that gravy is so much better when you have some real bones and meat to work with. Normally, that means using the turkey neck and giblets to flavor the broth while the turkey roasts. You can still do that. But this time, you can add the entire turkey’s back to the mix, resulting in a far more flavorful broth with which to make your gravy.

The Drawbacks to Spatchcocking

To be honest, there aren’t many drawbacks to the method. For some folks, the primary complaint will be that a spatchcocked turkey simply looks wrong. It arrives at the table with its legs splayed open in the most vulgar fashion.

To those folks, my advice would be to carve it in the kitchen, following our handy video below…

How to Carve a Spatchcocked Turkey

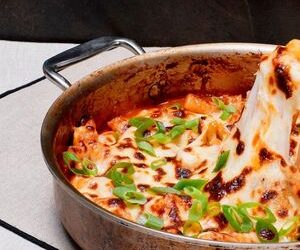

…and bring it to the table looking something like this:

Serious Eats

Ain’t that purty?

Other folks complain that you can’t stuff a spatchcocked turkey, and that’s true. However, you can start your turkey in the oven resting directly on top of a large tray of stuffing, transferring the turkey to a rack in a rimmed baking sheet about half way through cooking before the stuffing has a chance to start burning. This is actually an even more effective way of getting turkey flavor into the stuffing than to stuff it into the turkey itself. After all, you can only fit a few cups of stuffing at most into the cavity of a whole turkey. When butterflied, you get direct contact between far more turkey and stuffing than you ever could otherwise.

The final disadvantage is that if you’re not careful, the pan drippings will start to scorch, smoking out your apartment as the turkey roasts. There’s a very easy solution to this: just add a layer of chopped vegetables underneath the turkey as it roasts. (I use onions, carrots, celery, and thyme leaves, but you could add other things like parsnips, fennel, or garlic, for instance.)

Not only will these vegetables add aroma and flavor to the turkey, they’ll also emit enough steam to effectively control the temperature of the baking sheet, preventing any juices from burning. This is good news, since you’ll want to add those flavorful juices to your gravy anyway.

And if anyone pipes up and tries to claim that they want a traditional-looking bird, just shove a drumstick in their mouth and they’ll keep mum. A perfectly juicy, cracklingly crisp drumstick, that is.