The South really is the Italy of America. The cuisines of both are deeply regional and close to the farm. They share ingredients and a love for playing out life, the best and the worst of it, at the table. Those similarities weren’t on Jacques Larson’s mind when he first moved to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1996. He wasn’t cooking Italian food then, and he admits he knew little of Lowcountry foodways. So he spent his early years as a sous chef at Peninsula Grill, one of the first Charleston restaurants to specialize in Lowcountry cuisine, mastering dishes that define the region, such as hoppin’ John and she-crab soup.

Larson’s dedication to Italian food began when he decamped to Greensboro, North Carolina, to run Basil’s Trattoria and Wine Bar. From there, his path was set. He returned to Charleston in 2002, cooked for a few more years to great acclaim, and then left again to study in Mario Batali’s New York kitchens and in Italy’s Piedmont region. Back in the Lowcountry, his ability to blend both worlds blossomed at Wild Olive Cucina Italiana, his restaurant set among the farms of Johns Island. In 2014, he opened a second restaurant, the Obstinate Daughter, on nearby Sullivan’s Island.

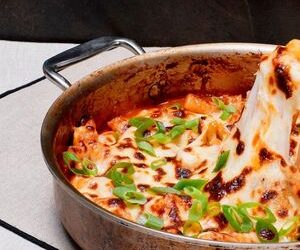

One of his signature hybrids is a variation on shrimp and grits. Traditionally the dish, which comes from the Gullah Geechee culture, includes shrimp in a sauce enriched with cream and bacon or sausage, enlivened with tomato, and then draped over grits. Larson’s rustic Italian interpretation begins with ’Nduja, a spicy spreadable salami. If you can’t find it at a specialty shop, you can substitute fresh chorizo or even andouille. The key is heat. Larson marries blistered cherry tomatoes with white wine, fresh spinach, and butter. The star, of course, is big Carolina shrimp. “One of the coast’s greatest resources,” he says.

Johnny Autry

Johnny Autry

All of this is spooned over crispy-fried slices of polenta, grits’ Italian cousin. Either will work in this dish, but coarse-ground yellow polenta holds together better when fried. That the two ingredients can swap places, like many Southern and Italian staples, is the beauty of being a cook in the Lowcountry, Larson says. Just don’t expect him to apologize to purists who say his dish doesn’t much resemble traditional shrimp and grits. “Those are good, too,” he says, “but they need to taste this.”